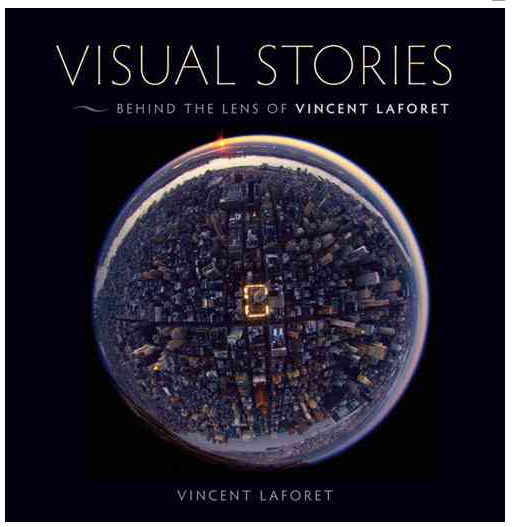

My First Solo Book: VISUAL STORIES

I’m proud to announce my first solo book: VISUAL STORIES.

I’m proud to announce my first solo book: VISUAL STORIES.

The book is available now for pre-order and comes in both eBook and as a printed book of course, and will hit the shelves on November 14th.

I’ve been a included in more than two dozen books over the years – but this is the first one that focuses on my photography.

VISUAL STORIES is effectively a look back through 18 years of my work as a photographer for The New York Times, Time, Life, Newsweek, National Geographic amongst others, as well as commercial, aerial, sports, and fine art photography. I didn’t want to write too technical of a book – so I decided to focus more on the stories behind the images, the thought process and often the psychology involved in making the photographs. I talk as much about the "why" as I do about the "how" if you will.

I wanted to write a book that included the details that I loved to read when reading other photographers’ books. I found that while I loved to know what lens they’d used to make some of my favorite photographs, I was more fascinated with how they got to making that photograph, the thought process and stories behind them (or luck) and what they thought of those photographs after the fact. Those stories always fascinated me most.

What I’m most excited about is that a few people who are NOT photography enthusiasts have told me that they really enjoyed reading it.

So if you’d like to know what it felt like (and what went on in my mind) when I shot from the needle of the Empire State Building, or made photographs of The Super Bowl, landscapes and aerials all the way to covering the Olympics and the aftermath of hurricane Katrina – you just might enjoy this book. I do address technical details of course and the metadata is included under each image. There is also a DVD included with more than 2 hours of video of me discussion many of the images beyond what you’ll read in the book.

Below are a few excerpts from the book that spans 264 pages and includes more than 100 images. Both are available for pre-order now.

Here is a link to the hard copy: Visual Stories: Behind the Lens with Vincent Laforet (HARD COPY)

And a link to the eBook version: Visual Stories: Behind the Lens with Vincent Laforet (eBOOK)

Lastly, here are two excerpts from the book:

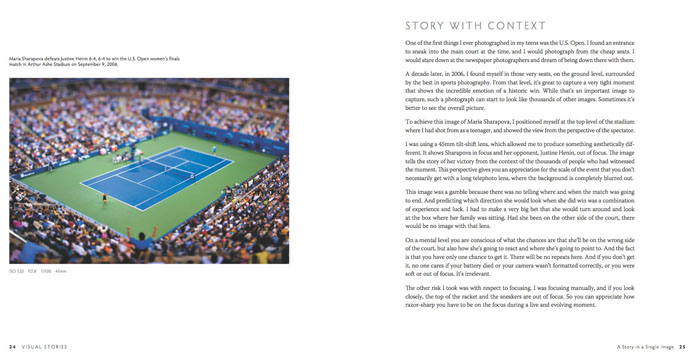

"One of the first things I ever photographed in my teens was the U.S. Open. I found an entrance to sneak into the main court at the time, and I would photograph from the cheap seats. I would stare down at the newspaper photographers and dream of being down there with them.

A decade later, in 2006, I found myself in those very seats, on the ground level, surrounded by the best in sports photography. From that level, it’s great to capture a very tight moment that shows the incredible emotion of a historic win. While that’s an important image to capture, such a photograph can start to look like thousands of other images. Sometimes it’s better to see the overall picture.

To achieve this image of Maria Sharapova, I positioned myself at the top level of the stadium where I had shot from as a teenager, and showed the view from the perspective of the spectator.

I was using a 45mm tilt-shift lens, which allowed me to produce something aesthetically different. It shows Sharapova in focus and her opponent, Justine Henin, out of focus. The image tells the story of her victory from the context of the thousands of people who had witnessed the moment. This perspective gives you an appreciation for the scale of the event that you don’t necessarily get with a long telephoto lens, where the background is completely blurred out.

This image was a gamble because there was no telling where and when the match was going to end. And predicting which direction she would look when she did win was a combination of experience and luck. I had to make a very big bet that she would turn around and look at the box where her family was sitting. Had she been on the other side of the court, there would be no image with that lens.

On a mental level you are conscious of what the chances are that she’ll be on the wrong side of the court, but also how she’s going to react and where she’s likely going to look towards. And the fact is that you have only one chance to get it. There will be no repeats here. And if you don’t get it, no one cares what the reason was – if your battery died or your card wasn’t set or formatted correctly, or you were soft or out of focus. It’s irrelevant.

The other risk I took was with respect to focusing. I was focusing manually, and if you look closely, the top of the racket and the sneakers are out of focus. So you can appreciate how razor-sharp you have to be on the focus during a live and evolving moment.

Despite those challenges, the photograph conveys the story of how Sharapova at this particular moment is at the center of the world, especially at the center of the tennis world, and that Henin is completely irrelevant and out of focus. The front page goes to the winner. The one who loses either never makes the paper or gets buried in history."

Click below for another example –

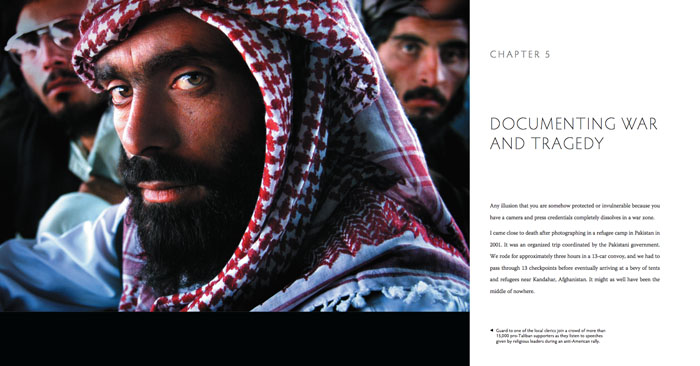

"Any illusion that you are somehow protected or invulnerable because you have a camera and press credentials completely dissolves in a war zone.

I came close to death twice in the weeks following 9/11 – in this case after photographing in a refugee camp in Pakistan in 2001. It was an organized trip coordinated by the Pakistani government. We rode for approximately three hours in a 13-car convoy, and we had to pass through 13 checkpoints before eventually arriving at a bevy of tents and refugees near Kandahar, Afghanistan. It might as well have been the middle of nowhere.

We were an incredibly disruptive force, media personnel from all over the world making photographs and trying to interview people with the aid of interpreters. The hard part was trying to find moments that looked somewhat authentic and genuine amid this gaggle of photographers and reporters.

In this image, two women are walking away from the press. The bright colors of their traditional garb clashed dramatically against the plainness of the sand. The way the monochromatic backdrop and sparse environment contrasted with their colorful clothing expressed the sense that they were facing a very empty future.

It was sad to see people leave all their belongings and end up in a situation where they didn’t have much more than tents, food and water coming from the United Nations.

At some point, one of the guards became unhappy that I had photographed something. I noticed his irritation, but I just kept doing my job. As we returned to our vehicle, I could see that he was following us. We were in the last car in the convoy, and I could see him riding parallel to us, pointing an M60 machine gun in our direction in a clearly aggressive manner.

We had made a big mistake being the last car in the convoy.

The gates that secured the camp closed at the first checkpoint, and we were separated from the rest of the convoy. We suddenly found ourselves surrounded by about 30 military men with AK-47s. The rest of the convoy continued on without us.

I pulled out my cell phone only to discover that I had no signal. I understood right there that even if I’d had a signal, George Bush wasn’t going to answer; and even if he did, the Delta forces would never come to save us.

Thirty guys with guns surrounded us and there was absolutely no one who could help us at that moment and at that place. It’s at moments like these that you immediately lose the illusion of being invulnerable. The fact that you might see yourself as some unarmed idealist or objective observer doesn’t mean much of anything at that very moment. These men with guns just don’t care about your ideology, your job, or your beliefs.

I never felt more alone than at this moment in my life.

Thankfully, a female reporter from the Chicago Tribune started screaming at them in their dialect. She spoke Pashto!

They were not used to being screamed at by a woman, let alone a Westerner, and they certainly didn’t expect to hear her speaking in their own language. They were completely disarmed.

She convinced them that my fancy digital camera had already transmitted the photographs back to Washington, and that at this point they were only getting themselves in more trouble. We explained they should have let the armed man who had fixated on me get in trouble, because now all of them were putting themselves in deeper water. After a very tense 25 minutes, they let us go.

It was the longest 25 minutes of my life. "

Congratulations on your first book 🙂 I will be reading this in not too much time I hope. I’m sure it will be a big success for you =)

Vincent Laforet Reply:

October 31st, 2011 at 12:29 am

That was quick! And thank you! The best thing I can say I guess is that my goal was to make this the type of book that I would want to read myself – and I think we pulled that off.

Congratulations. Really looking forward to reading this.

Matt

man my bank account is taking a hit this week!

congrats!

@Vincent Laforet, Quick by accident 😛 I saw it on Twitter after waking up. I think I’ll be ordering it later today 🙂

Congrats Vince. I will for sure be getting a copy of this for my photo book collection. Keep killin’ it brotha!

Vincent Laforet Reply:

October 31st, 2011 at 7:29 am

Thanks J!

Looks amazing! I can’t wait to get it. I’m so looking forward to it because, as you said-it’s great to know the lens and all, but it’s the story that inspires me. Best of luck 🙂

This looks fantastic! Congratulation Vince! I’ve just pre-ordered the hardback copy. I can’t wait!

Congrats Vince…I hope this is the first of many! Cheers, Jim

Vincent Laforet Reply:

October 31st, 2011 at 7:28 am

Thank you so much Jim – I do believe that one of the images of Sosa hitting his 66th home run may have run by your eyes prior to being published in SI!

Meny Compliments!

Huge congrats! I’m sure it’ll sell many copies! I’m sure you have tons of awesome stories. Really looking forward to snagging a copy for myself.

Looks like I’m going to need to make room on my book shelf (should I categorize under “L” for Laforet or “B” for Bad@**). I remember you talking with you about your time in Pakistan over a beer many years ago in Bowling Green. Even 10 years later the image above, and those pink fluorescent lights, still pop into my mind whenever your name is mentioned. Can’t wait for the refresher course.

Vincent Laforet Reply:

October 31st, 2011 at 12:41 pm

thanks Brett…

So excited for you Vince! Can’t wait to check out your book!

Vincent Laforet Reply:

October 31st, 2011 at 12:40 pm

Thanks Shawn!

Great story Vince. I always wanted to know what those pictures meant to you and what you wanted to get from the reader. I am buying this book as soon as I can. Thanks for changing my life of photography and other thousands! Mike Ross

Vincent Laforet Reply:

October 31st, 2011 at 12:39 pm

Wow – not sure if I truly changed your life – but very honored to have influenced it! (hopefully positively! 😉 Very much appreciate it!

Congratulations Vincent! I’m just about done with a living room remodel and this will make for a perfect conversation starter on the coffee table. I can’t wait to read your thoughts, highlights, and comments. You really inspire me to push myself and I sincerely want to thank you for everything you do.

I was waiting for such a book and I am pre-ordering it immediately.

I owe a lot to Vincent Laforet (and also to Joe McNally and Chase Jarvis) for being an unbelievable source of inspiration and knowledge. Whatever you guys do, I will actively support it (and if you ever come to Greece -for a vacation or an assignment, I am here to help you with local information and insight).

Vincent Laforet Reply:

November 1st, 2011 at 11:52 am

I’d love to come to Greece – man I need a vacation!!!!

That’s going on my christmas list!!!

This is awesome, I think I know what I am asking for this Christmas.

I am also looking forward to your presentation on Monday night here in Chicago at the Apple Store.

Vincent Laforet Reply:

November 3rd, 2011 at 9:23 am

Looking forward to it as well! It will be my first talk following tonight’s Nov. 3rd events at both Canon and RED!

Congratz Vincenzo. Did not know about your book. Looking forward to getting a copy signed by the gran bastardo!

I think that is amazing publication. Congratulation!

Vince,

Congratulations on your book and other successful endeavors. Your energy is inspirational and, hopefully, contagious.

Writing my list to Santa as we speak!

Looks great Vincent! Cant wait to have a read.

Vincent congrats on ur book. Couldn’t buy a copy till now as I’m without job for the last two months. Hope to have it one day.

All the best to every one of your new ventures.

Vincent Laforet Reply:

November 25th, 2011 at 6:02 pm

Good luck w Work REGI! Peaks and valleys my friend!

Hey Vincent, your book is changing my life by the page. Its great to read about how you took those photos and what they meant in which those photos made me want to be a photographer in the first place. It’s a great Christmas gift I got from my girlfriend and she get’s jealous about it, but in all fun! Thanks brother.

Vincent Laforet Reply:

December 26th, 2011 at 3:12 pm

What an incredibly kind comment – thank u ! V

Vincent you are the MAN