Can personality trump talent when selecting crew?

A few weeks ago I wrote about how trying to balance managing and directing with friendship can be a tight-rope walking act.

In this post I wanted to talk about something that is seldom discussed by people on the hiring end of the equation, i.e. from the perspective of a producer/director/DPs etc, I wanted to highlight how certain personality traits can very often trump talent when a crew is assembled.

Simply put: Talent and/or skill are extremely important in any field, and notably in the film and photography world, but it is but one of many important variables that most manager take into account during their hiring process. Below are a few key examples I’d like to share, the majority of which I learned from personal experience and more often than not: the hard way.

Low Maintenance often trumps talent:

The first lesson I learned in my professional life with regards to this took place when I was 16 years old. I was working at the Gamma Liason photo agency in the library pulling files. My job involved running around the library to retrieve contact sheets and slides when they were requested by sales agents for potential sales to magazines around the world. This also afforded me the opportunity to look at hundreds of photographers’ work from around the world of all different levels of skills.

At one point I noticed that one local photographer who clearly had superior work wasn’t getting hired nearly as much as another photographer who’s work was relatively lackluster

I sheepishly asked the assignment editor why she kept hiring the “lackluster” photographer over the photographer we mutually agreed had a significantly better eye.

“The [lackluster] photographer returns his pages in under 5 minutes,” she said. “Every time.” She continued: “The other one is always busy, and angling to see what the assignment is prior to accepting it, and I simply don’t have the time to deal with that for a lot of bread and butter assignments. If it’s something special I might make the extra effort, but I simply have too much to do,” she explained.

Basically, this wasn’t just a case of “the early bird gets the worm” it had a lot to do with the more “talented” photographer being effectively too "high maintenance". Simply put: he added stress to this assignment editor’s life, as opposed to making her job easier.

The “lackluster” photographer was cleaning house and getting assignments with a 5 to 1 ration over the other photographer, because he simply answered his pages (these were the days before cell phones or e-mail 😉 ) and did the job reliably with little fanfare. Every time. No muss. No fuss.

This was a key lesson for me early on. Basically: always try to find a way to RELIEVE STRESS for those hiring you. Even if you’re slammed with work – answer your phone calls immediately. If you’re successful and super busy: make sure you hire someone to do so for you.

When you think about it, it’s actually quite obvious but easy to overlook: When you don’t get back to people quickly it unfortunately sends the message that you don’t value them as much as what you are currently doing. Sometimes you don’t have a choice because you’re 100% committed to your current job, and it can be a very difficult balancing act to get back to potential new clients when you’re busy working for current ones, but even calling someone to tell them you’re in the middle of a job, and asking if they have the luxury of waiting for you to wait for you get back to them later can save you a job.

A few weeks later I remember overhearing the extremely frustrated “talented” photographer complaining to one of the sales agents: “Why in the world do they keep hiring the “lackluster” photographer over me!? My work is SO much better than that guy’s…”

Well that ego coast him tens of thousands of dollars a year unfortunately. Humility never hurt anyone. And it had (mostly) to do with his adding stress to the editor’s life by not answering his pages on time – it had little to do with talent.

His ego got in his way of the simple solution: asking the assignment editor with humility if there was anything he could improve on his end, in the hopes of getting more work. You’d be surprised how taking the time to ask such as simply question can be so effective – and how most people unfortunately revert to complaining or whining instead and to their own detriment.

More recently I’ve found myself in a position to hire people on a pretty regular basis, either as a Producer, Director or DP. Obviously I’m always looking for the best talent I can get. Nowhere does the management principle of “surround yourself with talented people” apply more than in the film industry. There should be an addendum to that though:

Find people that are both talented/skilled and that have a predisposition to helping relieve stress, not creating it.

When things break down, when the weather turns foul unexpectedly, when a piece of gear fails – there isn’t always a clear, easy solution unless your part of a medium to large production with backup solutions on the ready.

I can tell you with absolute certainty that you will make yourself a quick favorite, if you deflect the stress of the situation and simply find a way to solve it, or at least offer up a quick alternative to “make things work.” Sometimes even when you don’t have a solution, a smile or an appropriate joke to diffuse the situation can work wonders to keeping the crew’s morale high. People who have those types of personalities or skills are worth their weight in gold.

The ideal situation is to have the managers, and producers who plan for all potential issues that might come up of course – but most of us live in the real word, one that often involves a dude with the last name of Murphy.

Producers can have plans for bad weather or excessive heat. They can have shelter for crew and backup gear in case things break down. (There’s no excuse for not having a tent, plenty of water, ice and sun-tan lotion when you’re shooting in 104 degree weather in a populated area for example: you have to protect your crew.)

Those who complain or have a negative attitude will likely never work for you again.

When things are FUBAR (look it up) stating the obvious helps no one. We all know it. It sucks. Deal with it and carry on. Or as the Brits said during WWII: “Keep Calm and Carry On.” I’ve never understood people who complain about things that simply can’t be changed.

To be clear: it’s equally important for crew members to bring issues up to their department heads when issues pop up – and ideally in a way that allows the production to stay on schedule. The caveat is that like most things in life: “Timing is everything.” There’s a time and place to make suggestion – but almost as importantly: a time not to. Obviously any safety issue should freeze a production in its tracks the moment is becomes apparent. Other than that: we all have to try to find a way to make things work together.

The tone in which you bring an issue up is also critical.

The problem in front of you is obvious to everyone, but it’s likely causing a chain reaction of problems for production that you may be unaware of: (Click on the link below to continue.)

What crew members sometimes forget, is that the producer, directors etc. often have a bevy of things to deal with that the crew isn’t aware of, and that needs to be addressed on the spot when something unexpected happens.

Often, the “problem” at hand has just instantly created multiple layers of other problems (a chain reaction) that you aren’t necessarily aware of. And in those circumstances, when the blood pressure can sky rocket with some, managers are in search for a solution and/or someone to help relieve that pressure – not add to it.

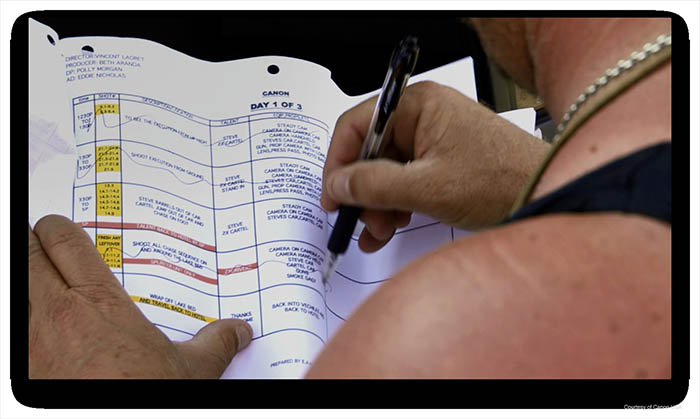

When a generator went out at 11:45 p.m. on a Saturday night on a night exterior scene in LA on a job a few years ago – we were in deep trouble. I had asked for a backup generator but the producers had decided that they couldn’t justify the expense given the budget they were working with.

Our gaffer made a few calls and was able to borrow another generator from a production that had their backup close by, while the rental house took 2 hours to get our back up generator to them in time for their shoot. As a result we only lost and effective 30 minutes thanks to that gaffer, as we were able to work on setting up the next shot, blocking it out, rehearsing it, and nailing it on the first shot and moving on. I have worked with that gaffer every chance I can get, ever since. He’s also incredibly talented – and obviously cool as a cucumber under stress.

One other note is to keep in mind is that crew members are more often than not kept in the dark and are unaware of a lot of the politics and budget issues that go on behind the scenes.

When you complain to a department head – God forbid in front of others – that “x” is missing for you to do your job, you may not know that that department head is well aware of that fact, and that she may in fact have fought the good fight, and lost.

The bad move she can make as a leader is to put her hands up and throw the production under the bus and say it’s “their” fault because it starts to break down morale. They sometimes have to hold to the party line and let you know that they are aware of it and are doing everything they can to rectify it. Because the producer who nixed their request might in fact be standing just 2 feet away… and they really can’t get into it in front of the crew – that would not only serve to break the chain of command, but would also lead lower morale and perhaps even signal to others that breaking the chain of command it "acceptable" which it never is.

When something goes very wrong, a producer, director, DP instantly has to consider all of the ramifications this has, and to do so on the spot. They have to consider not only how the problem affects the next few shots, but the shoot altogether, and possibly the next few weeks or months of logistics. It can be a lot to handle. They may have a blank look on their face because they’re doing through a hundred permutations of solutions of how to rework as scene or shoot based on the “problem” at hand – and it’s a lot to take on (but comes with the job.)

Another example this brings to mind involves a recent experience that involved my interviewing candidates for a Director of Photography position for a relatively high profile job. I went looking for top people and picked 3 candidates based on their work and reputation.

I called the one “hot” and extremely talented DP first, but within the time it took him to get the first sentence out of his mouth, I knew that it would not work when he said: “Listen, I only believe in working with the early morning light, and afternoon light. Everything else is a waste of my time.”

It wasn’t just what he said. It was the way he said “my” to be honest. I knew instantly this was a “no go” just based on the use of that word, let alone the tone that accompanied it. Had he used the word “our” it would have been a small step in the right direction.

The truth is, in an ideal world without budget restraints, he’s absolutely correct. This is exactly what Terrence Malick did in “Days of Heaven” and it’s an epic film as a result. (And it drove his Hollywood crew crazy btw – because they had never worked that way. They nearly rioted.)

But even if I did have that luxury – I would not have hired him based on his attitude and the hints about his personality that his choice of the word “my” pointed me to. His arrogance got the best of him. He drank a bit too much of his own Cool Aid. Needless to say I moved on to hire someone else.

Recently, I had the opportunity to speak with Roger Deakins for a bit, and even though he is clearly one of the best Cinematographer working today, his ego is well in check. He doesn’t want to be in the spotlight, and he strikes me as someone who is eager to uphold the highest standards and to collaborate with others in making the most striking films with a strong visual style – note the use of the work “collaborate.”

Another lesson that I’ve learned the hard way: always trust your gut instinct about someone if the alarm bells go off at some point. No matter how talented someone is, if they come to set with an ego that isn’t in check, it usually only serves to cause an imbalance amongst your crew which can grow like a cancer.

With each budget come certain realities and likely guarantees:

Know and accept the realities of a job and the budget that comes with it – on both side of the hiring equation.

It’s very important for the producers/Directors/DP to communicate the realities of any job with those they are hiring. Bigger budgets have certain perks and of also come with a likely set of challenges too. Smaller budgets will by definition have to cut corners here and there, but can also be much more nimble and creative.

The worst thing you can do is mis-represent the realities of a job to someone you are hiring. Be up front if you are shooting in July and know you will be shooting long days as you try to catch both sunrise and sunsets for the film and/or for time lapse sequences for example.

Have the discipline to create down time in the middle of those days and let the crew rest when the light is terrible and the heat unbearable – because the summer days are the longest of the year, and therefore trying to capture BOTH a sunrise and sunset means a very, very long day, that when combined with prep, setup, shoot and post can easily lead to a 16-18 hour day.

This can be deadly on a crew that isn’t ready for it – especially if you repeat the process over several days. The best thing to do is to plan time for rest, days off in between a series of long days, and plenty of water and shelter in those hot and sometimes humid environments, a fact that just by itself can lead to physical exhaustion.

If you simply don’t have the budget to support time off midday, or days off in between back to back shooting days – communicate that clearly to your crew ahead of time before you hire them. If you don’t it will backfire. Guaranteed.

On the other end, if as a crew member you are aware that a certain director or production house has a history of working these types of hours and long days: know what you are getting yourself into. Politely ask the line-producer how many hours a day they are planning for, and if there is overtime in the budget. Make sure that you both agree on either a 10 or 12 hour day, and that you work out what happens if you have to go over. If you don’t discuss this up front, it can lead to an unbearable situation for all involved.

I personally have no problem with people who tell me they want to work a maximum of 10 or 12 hours a day. As long as they tell me so before the shoot – not in the middle of a job. I respect people who have families, or have been doing this long enough not to want to work 18 hour days back to back. I can plan around those types of request in advance – given the notice. I can’t come up with an easy solution when I find out about it on set in on the first day of a shoot.

While rare, some producers tell their crew that they are going to pay them higher rates if they agree to work these kinds of hours and everyone is happy. I think being up front about this BEFORE the shoot is of pivotal importance.

Know who are getting yourself involved with, study their past actions, and GET IT IN WRITING:

It goes without saying that as an employee, you should be weary of less experienced producers / production companies / directors who will not be able to hold to their word. Have a simple deal memo in writing via e-mail when you negotiate your day rate, and make sure it’s based on a specific number of hours, and also make sure to address what happens in terms of overtime and what that rate is should you go over. That way it never becomes personal and there’s no grey area – do this over e-mail, NEVER over the phone.

Moving up, and moving back down within a hierarchy:

Another thing I keep an eye for when hiring people is to make sure that they are clearly happy in their current position. The film business is based on a hierarchical system and on working your way up from one job up to the next level of job. A film loader will go to becoming a 2nd AC, then 1st AC, then possibly an Operator, and then DP for example. If you hire a 1st AC who also does quite a bit of DP work on her own, make sure she is still happy being an AC and doesn resent having to do that work. It sounds very obvious, but again, it’s critical.

When someone regularly works as a DP and you ask them to be a 1st AC on your team, keep in mind that if they don’t know how to keep their ego in check, problems might develop especially if they start to disagree with the DP on the job and/or try to do things that normally a DP does that would otherwise not be in a 1st AC’s job description.

That being said, when people remove ego out of the equation, they can become incredible assets, because they have the experience of being a DP, but are happy doing the job of 1st AC because it involves a different set of skills and responsibilities. Just as importantly, their experience as a DP helps them to better anticipate what the DP they are working for on that job might need, and to be one step ahead.

There’s nothing better as a DP for example to realize you need a certain lens or filter, and to look back and see your 1st AC with that lens or filter at the ready – and without a hint of smugness about it. You will find that you both enjoy working together when you’re on the same wavelength and can both make your days, and work more efficiently, not to mention create better work together.

Generally speaking, when you go up to a higher position in any hierarchy, that comes with certain set of new responsibilities and perhaps a bit more stress. It can be extremely relaxing to take a step or two back down that hierarchy for some, and to do a job that absolves oneself of a lot of those stresses.

Final word:

When you hire someone, take the time to do a little research and to call someone who may have worked with them in the past. If you don’t get a glowing recommendation, or don’t hear something positive from the other end of the line: that’s a sign.

When you are about to be hired by someone, do a little research as well and find out how the previous work experience was for some of your colleagues if you can. History tends to repeat itself.

And lastly, understand that we all work a wide variety of budgets and job types these days. I work jobs where there is a fancy chef doing catering and walking around with amazing snacks every few minutes. I also work jobs where there meal of the day is a choice is Tuna, Turkey, or Veggie Subway Sandwiches. But if I do my research and know which one it’s going to be ahead of time: and I commit to the job with that knowledge in mind, and it’s all good. For me at least.

Every time that I take a job, or that I put one together as producer, I am building a reputation with those I work with, a track record if you will. I never ever forget that regardless of what side of the equation I’m on.

This is a business where most hiring decisions are made based on recommendations – not resumes or IMDB credits or awards. That alone should tell you something as to whether or not personality trumps talent…

Always try to keep these things in mind – and hopefully you will be rewarded long term for having“found a solution” to a problem, or simply having kept a smile on your face when things took a very bad turn.

Tags: Managing

Probably one of my favorite posts by you. Thanks!

Vincent Laforet Reply:

July 12th, 2013 at 10:33 pm

Thanks Jeff! This was a rough draft actually and wasn’t meant to be published… guess this is what you get for working on WordPress on a plane’s WIFI! Still rushing to add pix and catch spelling errors…

Great post Vincent! I think you have some great insights into production world that are valuable. I love reading your stuff. I am just starting to get into larger production work and am trying to absorb all the knowledge and experience from people like you that I can.

Thanks!

I’ve been an admire of your work and this blog for sometime but never commented until now. I’m delighted & encouraged by this article since I’m about to embark on my directorial debut with a screenplay I wrote. I couldn’t agree with you more Vince, an ego must be in checked when collaborating on any venture worth perusing. Based on what you wrote, I’m glad to know you have the same mindset as I do.

SWG Reply:

July 13th, 2013 at 3:08 pm

@SWG, My apologies for typing fast & not checking my spelling.

Line 3: in-check

Line 4: pursuing

Humility seems to carry you the furthest in any environment. When you work with people who understand other people, it’s such a better place.

I’m a nineteen-year-old who has been learning and exploring in filmmaking for four years now. I have mostly worked in the Nashville area, but I am moving to LA this fall to work for a director whom I know. I really want to round out my knowledge and get a feel for the industry, so I am considering volunteering. From your experience, what do you recommend to someone just starting out? You mentioned some great points above. As you’re starting out, what are some good practices you should use to learn and grow as a filmmaker without getting in the way or having to be babysat on set? I know there’s no one way to do it, but having the right attitude helps–and insight always helps at some point along the way.

-Adam

Vincent Laforet Reply:

July 12th, 2013 at 10:32 pm

Simple advice: be sponge. Listen. Don’t talk. When the time is right – then ask if you can have a conversation and dig deeper. From your writing it seems like you already have a finesses with the way you do things – you’ll be fine. Good luck!

Adam Stuart Reply:

July 14th, 2013 at 6:44 pm

@Vincent Laforet, Thank you!

thanks for sharing these thoughts. i got to see them in practice over 2.5 years ago and learned my failings in this category through that experience. my time/experience since in the industry has only proven these points true; I hope more people pay heed than not!

Not just a good post, but a GREAT post.

When I first got into making films, a successful filmmaker taught me that “Not Cool is Never Good”, that 15 minutes early is “on time”, and that interns can be replaced at any time, for any reason, because he could always find more.

George Lucas described making the original Star Wars as “controlled nightmare”.. it’s hard enough when your crew’s not working against you.

Really great article – very insightful!

Vincent, that was ABSOLUTLY brilliant and invaluable. Your advice is so concise and applies to the amateur or the seasoned professional. I cannot wait to share this post with people.

Thank you for writing it!

One of your best posts ever, Vincent. I couldn’t agree more. There are way too many people who don’t get this when they are starting out (some also much, much later).

Spot on. The days are simply too long to be working with people who A) aren’t difficult and B) can’t handle problems calmly. You can always teach skills, but teaching humility, patience, and how to be a decent person isn’t likely.

Great post Vincent! Totally true!

I understand what is being said here, I really do, but there are also some points that might be missing, depending on your point of view of course.

You mention to Adam Stuart to “listen” and not to talk which I find to very confusing. Looking at a lot of movies, TV shows, commercials, etc from the outside what was needed was somebody to step up and say “this is terrible and it needs to change”.

Case in point being movies like Prometheus and Ocean’s 13, TV shows like Revolution and Alcatraz, etc, etc. All have big names (production and cast) attached and they are all, demonstrably terrible in many many ways.

Can’t help but thinking that these big ticket productions (as well as smaller ones) are being made and being ruined because somebody didn’t say “Hey! do you really think a scientist would reach out and try to tickle a scary looking space snake? Also, the plot of this movie doesn’t make any sense Mr Scott!”

Getting the job done is important of course but getting it done well and getting it done right are not always the same thing and sometimes a bit of friction or strong counter-point can be just as good as everybody getting along.

Vincent Laforet Reply:

July 13th, 2013 at 9:27 am

No no – you’re misunderstanding. Definitely speak up! We all need to!

He was asking what the best thing he could do as a student is (if I remember correctly) and I answered: to listen, be a sponge, and I should have added: to have a positive attitude. Most students are too busy talking these days – not listening.

Charlie Reply:

July 15th, 2013 at 4:01 pm

@Vincent Laforet,

I think you had the right advice the first time.

@Neil

The time for those discussions is long before you get to set. On a student production, maybe you have time for creative ideas while shooting. Otherwise, look at the first rule above: relieve stress.

Resolve plot issues while discussing the script, not on set. If you didn’t get a script, they don’t want to hear your ideas.

A 2nd AC can say something to the 1st AC, not the director. Exception: safety. If you see something about to fall, or a cable running through a puddle, you should immediately tell the appropriate person.

Great post Vincent. Thanks for sharing!

Thanks for taking the time to share your experiences and give sound advice. I have been in the film and photography world for about two and a half years and wise words from a seasoned professional are extremely helpful and appreciated. Thanks again!

I get the point to always be aware of what you were hired to do and do it with a smile. It seems so cliche, but it is so true. A smile with good decision making skills, especially at times of an immediate and unexpected shit storm, is priceless…lol…especially when reputations and money are on the line.

The director was hired to direct, and the truck driver was hired to drive the truck for a reason. And I think comfort with your role speaks volumes about personal confidence and emotional intelligence.

I understand with a high-dollar production that requires literally hundreds of people, a crew full of directors could be especially irritating…”good god, WTF were you thinking Ridley!!!” by every other crew member at any time would be heinous…or just after a shot was set up that too hours, the grip is yelling “this is ALL wrong Ridley!!!!! what were they thinking when they hired you for this picture!!!”. It might funny to watch though from a distance, and maybe there is an SNL skit in that somewhere…”the disgruntled crew member”…lol.

Having said that, I still lean a little towards what Neil was mentioning.

Maybe its just a fantasy by i hope there is a team or company out there that exists and maybe on a smaller scale, that encourages input from any level if its a good idea. And that a high level of collaboration exists from top to bottom. I think it would have to be loaded with cross-functionally competent people that didn’t mind shifting roles as needed depending on the project. And if you would have to put your money where your mouth was, or people wouldn’t take you seriously anymore, but it would be nice if a mistake or two wasn’t career threatening and interjection was still encouraged despite a stumble or two.

Maybe it is just unrealistic or too costly to make any mistakes, or maybe i have to assemble the team myself to show it works, but i do think it is possible if this style of production was considered from the get go.

Crew members with bad ‘tudes are just as bad a leadership with bad ‘tudes. And ultimately i think organizations are more productive with transparency within limits and with the right team members.

Feel free to call BS on this, but I still believe! Lol…

Neil, I have ruined my copy of “Do androids dream of electric sheep?” because I have wept all over it…because of you…lol…

Cheers.

Very helpful as always, thanks for sharing.

Excellent article – a perspective too many people who can’t find work simply don’t get!

Thanks for sharing!

To answer the question this post poses… Of course it can! How do you think I continue getting work?!

There’s been a lot of academic research on team performance, and one thing that keeps on being shown again and again is that teams with a lot of experience together invariably out-perform a team of “stars.” As you say, selecting your team to work together well will often times trump raw skill and talent.

I need a coffee mug with “Keep Calm and Carry On.” on the front of it and “I’ve never understood people who complain about things that simply can’t be changed. The tone in which you bring an issue up is also critical… Whining, complaining, let alone screaming is unacceptable. “ on the back! It’s like it was pulled right out of my mind! Thank you!